A pair of American skiing pioneers skied up Mt. Mansfield, Vermont in 1946, skied down to settle a bet, and in the process created a race that’s remained true to the individual and communal spirit that sustains nordic skiing to this day.

At one point in time, skiing was simply a way to get from point A to point B.

Take stock of humans gliding on snow at this moment in 2022, though, and it can seem as if the world is too much with us. In Beijing, where the eyes of the world were recently fixed on skiing, trillions of dollars have been poured into constructing perfectly manicured laps that have increasingly become the sport’s preferred method of racing. Last week, the Olympic 30-kilometer women’s mass start entailed four laps of a 7.5 k course. The men’s 50 k race the day before was originally intended to simply up the lap count, six on an 8.3 k course. Then there’s the ever-dizzying array of equipment and disciplines.

The pandemic has seen the proliferation of alpine touring skis, and fights about who gets to use that equipment at what cost. Going from the metaphorical Point A of skiing – the individual euphoria and joy brought by juxtaposing the beating thrum of your heart and skis on the snow against the frozen world – to Point B – the kindred spirits who’ve taken the warmth generated and cultivated it into a genuine community – has become an increasingly difficult journey as those literal distances collapse on one another.

Perhaps then, it’s time to make the distance between start and end too stark to ignore. Perhaps, point A can be set at the tallest point in American skiing’s home state, and point B at the town center of its most quintessential ski village.

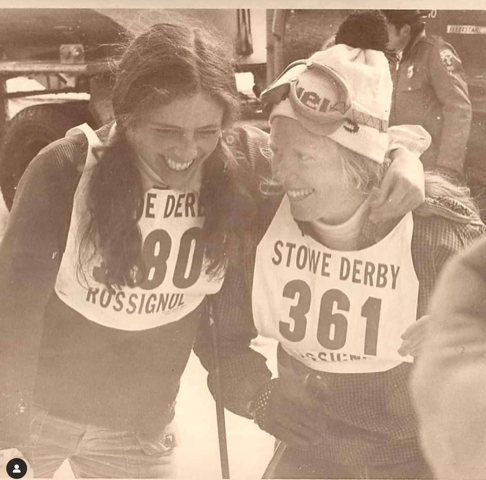

That’s just what the Stowe Derby intended to do when it was revived last Sunday in Stowe, Vermont.

The goal: hold a race with 77 year old history in a way that’s representative of the venue’s skiing culture and heritage, imparting it to participants who will be ready to spread it far and wide.

As race director Sarah Sterner said in an interview with FasterSkier, “Stowe’s heritage is a love of skiing. And not defining it beyond that. That’s what has lifted the Derby all these years, and it’s what we want the Derby to give people this year too.”

It all started as a bet

The Derby is part living history, and part tribute to the basic blocks that formed skiing in America. Telling its tale includes the key characters, in key places, and at key times, that came to define the sport we all do and love today.

That tale is oft-told, but not worn. It begins with two pioneers in Stowe in the early post-World War II period where optimism and inginuity spread to all corners and walks of American life.

Erling Strom was a Norwegian-born, American-made wanderer. After spending his childhood in Telemark, he landed in 1919 in Arizona, setting out to become a real life cowboy. His stint there though, was short. He set off for the high peaks of Colorado with his skis, where he grew into a last gasp of the old wild-West legends. He skied up Longs’ Peak, and later became the first person to ski up Denali. His feats landed him a job as a ski instructor at Lake Placid ahead of the 1932 Olympics, where he would spend the rest of his career and his life.

Sepp Ruschp landed in America as the threat of Nazism spread over his native Austria in 1936. He was a cross-country national champion in the previous two years there, and had written all 90 ski clubs in the United States at the time looking for a job that would allow him to flee. The Mt. Mansfield Ski Club in Stowe responded, and he became the head ski coach there, and at the University of Vermont, before turning around to serve his newfound country with the 10th Mountain Division in World War II.

When Ruschp returned in the winter of 1945-6, he and Strom were out skiing, scouting routes to erect a chairlift on the Mt. Mansfield slope above the town of Stowe. Prior to the war, Stowe’s ski trails had been a loosely defined set of forest roads put in as part of a Conservation Corps (CCC) project during the Great Depression. The first tow rope had gone up in the area in 1940, but Strom and Ruschp were of a generation where being proficient in backcountry touring, jumping, nordic and alpine racing were a requirement for a skier, and each had a quiver of skis including one or two pairs of hickory-made, pine-tarred, gliders.

The first law of the endurance universe held – put two skiers together and they will eventually start talking about gear. Strom and Ruschp decided to test what would be the best single-pair of skis to start at the top of Mt. Mansfield, race down the 2,500ft slope, and then across the valley into town to the steps of the iconic Stowe community church. To decide, they organized a race.

The first Stowe Derby ran on the last Sunday in February, 1946. According to an article in the Stowe Reporter from 1975, 12 men, all of whom were required to be over 35 years old, completed the 4.5 mile downhill on Mt. Mansfield, followed by the 5.5 miles across the valley to Stowe town. Sepp Ruschp won with a pair of nordic skis in a time of 1:03:36.

Over the next twenty years, Ruschp and Strom raced the same course every year there was enough snow on the last Sunday in February. The single restriction, one pair and only one pair of skis, came to define the essence and spirit of the Derby. The 5.5 mi cross-country jaunt at the end of the downhill meant that nordic skis, which increasingly were becoming narrower, tended to be the choice. In waves of 5, skiers would start at the top of Mt. Mansfield, and most would eventually wipe out. That proved to be a human interest story, and drove up the number of spectators from the town below. Under Ruschp’s coaching, a generation of alpine talent was emerging from the Mt. Mansfield ski club, with the skill of these skiers directly proportional to the appeal of watching them have to master the art of having their heel free on the slope of Mt. Mansfield. At a Derby during the 1950s, you could watch the likes of local kid (and eventual Olympic ski champion) Billy Kidd heading down the slopes.

The Derby hit a rough patch in the 1950s that nearly saw it become lost to the unpredictability of New England winters. After a few years off in the 1960s, Johannes Von Trapp (of Trapp’s Family Lodge) partnered with the Ski Club to revive the Derby in 1972, which marked the beginning of the Derby becoming a fixture within – and a distillation of – New England’s vibrant ski scene. By 1983, the Derby saw what then race director Dudley Rood called 700 “enlightened lemmings” lining up to hurl themselves down Mt. Mansfield.

The Derby had found itself at a perfect confluence in Stowe, and New England, at a perfect time. The sport of cross country skiing had got an injection of interest, especially in Vermont, following Bill Koch’s silver medal at the 1976 Innsbruck Olympics. The New England collegiate carnival circuit ended its race season on the last Saturday in February, which allowed its racers to hit the Derby the next day. The field which had started with two of America’s most accomplished skiers of their generation had somehow maintained its über competitiveness on a course that was increasingly absurd when considering the direction of the sport.

One of the skiers who joined along during these years was a man who became synonymous with Vermont skiing. Murray Banks helped found the Mansfield Nordic Club on the west side of Mt. Mansfield, and remembers clearly the “wool knickers, flannel shirts, and backpacks full of beer – ah yes, it’s the Derby” of the day.

Judging by the memories Banks can most clearly recount – the Derby in these years as much about what happened when the skiing went wrong as it did when it went well:

“[I remember] coming off a sweeping turn and seeing a skier from an earlier wave veering off the Toll Road, down a mogul run. A split second of indecision at Mach 1 and over I went with him. I like mogul skiing, but not on nordic skis. It was ‘Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride’ for a couple hundred meters…it was not uncommon to see people at the finish with blood on their bib in those days – an honor!”

The Derby made its only concession to the march of time in 1987, when the development of skate skis, which Banks noted “made things so much easier,” caused race organizers to split the race between a skate competition held in at 10:00am, and the classic Derby (on classic skis) held at the traditional 12:00pm start.

Even when conceding to time though, the Derby somehow made the development that kept it happily behind the times. In addition to adding the skate race, organizers also added a “Derby-meister” category – harkening back to the days of the “ski-meister” when jumping, cross-country, and downhill events in junior and senior ranks were scored cumulatively, rather than as separate disciplines.

The catch: to compete in the Meister category, skiers would have to figure out how to go from Point B to Point A, coordinating their own logistics to catch a ride back to the base of Stowe to take the chairlift up to the top again after completing the skate, and hoping to arrive before their classic wave started at noon.

Banks was there for the development, and recounts the asinine seriousness of it all: “[You had] to bundle up for the chairlift ride to the start, strip down at the last second trying to stay warm, deliver your warmups to the snow cat that went to the finish, and then start race one. Then it was cross the finish line and immediately jump in the car, change clothes and boots, run the chairlift, and just hope it arrived at the top before your bib was called to the line. You skied out the rigor mortis through the first few turns. Skiing fast on skate gear is one thing, and then doing it moments later with kick wax on takes some adjusting.”

The Meister though, in retrospect, seems like a natural extension of the event, rather than a new era.

Sooner or later, someone would’ve taken the sheer joy of trying to reign your energy and movement on snow into forward motion found on the slopes of Mt. Mansfield, then experienced the self-affirming grind of the ski into town, found a whole group of people who loved it too at the finish line, and said “we should do that again!”

As the Derby has gone on, that has been its mantra: “We should do that again.” First it was Strom and Ruschp repeating it, then a chorus through its first heyday (who’s brightest tenor was surely Murray Banks), and last Sunday, it was the intrepid voices of a new generation of Derby-goers and Derby-Meisters, ready to go from Point A to Point B via US skiing’s oldest, and most thrilling, route.

The Derby Runs Again

After the past few years in skiing, where pandemic and climate change have upended race calendars and race venues, the Derby that was held last Sunday felt like nothing short of a sign of hope.

It’s impetus was in the hard-work of Sarah Sterner, race director, who was responding to a simple concern: “My kids said, ‘Mom, there has to be a Derby!’”

Her vision for the Stowe Derby in 2022, though, quickly became one that was concerned with matching the full sweep of its spirit, “So much of this is about understanding the history and culture of the event – what did people love about the Derby before, what can we do to reboot the Derby in a sustainable way. Of all the Derby legends and lore, what do we need to scoop out the corners to make this go again and make it awesome.”

That included building around the event’s edges while keeping to the traditional long and short course. There was a revival of the legendary Derby afterparty, which Murray Banks recounted was “one of the best afterparties in ski racing!”

The prizes this year showed just how invested the Vermont ski community was in its oldest event. The winner of the Skate and Classic races received a full-on tuning setup from Caldwell Sports including sizing, grind, hot box, and hardening. For Juniors under 18, Pinnacle Ski and Sport in Stowe donated a new pair of Rossignol skis and poles. This version of the Derby also awarded prizes to those who could make the downhill run before town the fastest. The prime: a pair of winteralls from Ripton & Co.

The careful planning yielded the first successful run of the Derby in half a decade. Between all short and long courses across classic and skate disciplines, there were over two-hundred skiers that successfully navigated the course. That included five Derby-Meisters, who all came out of Sunday adding a little bit to their own personal legends.

There were no doubt spills and wipeouts that will still be talked about years from now, and a sense that after a New England winter that saw a foot of snow fall a week before this Derby, there is winter fun and spirit in droves that will sustain the Derby for years to come.

Ben Theyerl

Ben Theyerl was born into a family now three-generations into nordic ski racing in the US. He grew up skiing for Chippewa Valley Nordic in his native Eau Claire, Wisconsin, before spending four years racing for Colby College in Maine. He currently mixes writing and skiing while based out of Crested Butte, CO, where he coaches the best group of high schoolers one could hope to find.