Part I of FasterSkier’s interview with Cory Schwartz—retiring Head Coach at the University of New Hampshire—looked back at how Schwartz started in coaching, and the foundational events that drove his coaching philosophy. Here’s more of FasterSkier’s interview with Cory Schwartz.

Our discussions with Schwartz focused on the development of the UNH team culture, and how it evolved from his own experiences in trying to keep the ski program alive. “As I progressed through my early years of coaching, we were on the cutting block at least four times during my career,” Schwartz observed. “And that led us down the road of forming the team (concept) because we had to solve the problem together as a team. We just kept building on that; I could sense the experience made the team more positive and happier. That made them be better skiers because they wanted to perform together. It just went down that road, that this makes sense. That translated to even the practice part… that we’re better being whole and supportive instead of in these different disciplines of Alpine versus Nordic or men versus women.” That experience laid the foundation for the future. “I could sense that experience made the team more positive, happier, which made them better students and better skiers.”

The threat of the team being cut multiple times was always stressful. “It happened in a way that wasn’t always easy,” Schwartz remembered. “I once got a phone call at six in the morning saying I needed to come in; another time I heard about it on the radio. But each time, U.N.H. skiing got stronger. We learned what skiing meant to the State of New Hampshire, and the State rallied behind us, and they taught the University that skiing is the State sport. It made us develop a great foundation of alumni who support the team like no place else. Each time, even though it sucked, it made us better.”

Further proof of improvement through adversity and teambuilding is that the team now has grown to 40 members (Nordic and Alpine combined). But even a large team doesn’t mean that team building suffers. “We don’t do an A, B, or development team. What we do for our best skier and our slowest skier is the same. We support everyone the same. It’s a better experience for our skiers. We brought them (the skiers) here for an opportunity, to me that opportunity is let’s train, let’s be a team, and let’s race.”

When the program was first on the chopping block, instead of just getting mad, Schwartz took action. He reached out to the community and alumni. “I also reached out to politicians in the State.” But Schwartz refuses to take credit for saving the program multiple times. “It’s more than me. Prior coaches got involved. One of the things we did was rally a group of our alumni who were successful business people and utilized their knowledge of how to create a better business plan to succeed as a team. I think that’s what probably saved us.”

The fight for survival led to a more robust program with greater reach and impact. Schwartz acknowledges that the fight to survive, “is the only reason we can do this. We now think about things like we’re running a company, we have to figure out how to fundraise and promote and involve our Friends group.”

Reaching out to stakeholders to stave off elimination resulted in another positive byproduct: it built relationships which increased fundraising and improved the team’s resources. “We fundraise about $270,000 every year (for the combined program),” Schwartz calculated. “We’re utilizing about $350,000 every year between fundraising and payouts from endowments.” Without the threat of elimination, the alumni network which allows for these contributions would not have been possible. The support for the program is wide and deep. An example; in 2022, U.N.H. skiing received a $2,000,000 gift from former ski team Captain, Tom Putnam.

When Schwartz began coaching, he was close in age to the members of his team. Now, he’s two generations removed, but the age difference doesn’t seem to matter. “Now I’m older than their parents,” he said. “But I don’t think it’s a struggle for me. It’s amazing how focused (today’s students) are, and the stress that they either put on themselves, or the stress that’s on them, just to ski.”

The presence of phones is often a battle. “That phone…and I’m just as bad, the phone has really changed communication, keeping focused, because they’re ‘snapping’ all the time. Many times, (students) are texting me, and I say this isn’t something we should text about, we should talk in person. On the other side, I think being involved in this new era of social media has helped me think young. But I talk to them (students) all the time, when you’re in the real world and you want to talk to your boss, you don’t do that over text, you need to get in front of him or her and speak well.”

Schwartz has been around long enough that he can now identify reoccurring coaching themes. “Every spring we have to recreate what we are,” he said. “We can’t expect it to be the same unless we make sure it’s the same, accepting the new students, communicating, setting the standards of what you want in practice. I wouldn’t call that a challenge. You just have to make sure it happens.”

However, aging as a coach does demand a price to be paid. “The struggles are more internal, going on 65, I can’t coach the way that I used to. You can work around it, but at some point, it’s tougher on me mentally because I can’t do what I used to do years ago, and that’s one of the reasons I’m retiring.”

The physical challenge is only one of the reasons Schwartz decided to retire. “I’ve been doing this for 42 years, and at some point, you decide that you need to do something for yourself, like being home for Thanksgiving. I’ve seen too many coaches stay too long…there was no way I wanted to leave under those circumstances. I wanted to leave with the team strong and I wanted to leave in the place where I had relationships with my team. I did that self-reflection; I’m always energized when I’m around the team, and right now I’m excited for the recruits we have coming in.”

After Schwartz departs, he doesn’t want to be a shadow looming over the program. “My goal is that U.N.H. ski team succeeds. Any involvement that I have (after retirement) would be based on that. If they want me to help in any way, all that have to do is ask. But the new director has to realize that the success or failure of the team falls on his or her shoulders.”

Schwartz attributes his longevity to liking what he does. “I enjoy working with the people that we get to come to the University of New Hampshire. It’s satisfying. Not every day is perfect. It’s also satisfying to figure out what you have to do to change. I think that’s what brought me back. We had practice this morning. I love seeing them work hard. I love seeing them smile and interact with each other. It’s that whole part of being a team that has brought me back for 42 years…with success. I’m very proud of our team performance and individual goals.”

Schwartz never seriously considered moving on from U.N.H. after he had established himself. “The whole package of raising a family in the sea coast, that U.N.H. was my alma mater, I did not think of ever looking at another school.”

His longevity has meant that he has developed an impressively broad coaching tree of disciples with him as the root system. Those providing comments for this article are a small subset of Schwartz’s legacy. People going on to coaching, “that meant to me that after their four or five years at U.N.H., they still loved the sport, and they still had that focus to continue being in it. I remember at one NCAA’s there were I think seven (U.N.H.) graduates that were coaching at different colleges.”

Beyond social media and money matters there have been other big changes that Schwartz has seen. Recruiting is now different. “Unfortunately, U.N.H. has always had to prove that you can be successful here because we’re recruiting against the Ivies and full scholarship teams out west. We learned right away that we had to get the student here to show them what U.N.H. is, we figured that out right away. I have gone to Scandinavia twice to see what that’s like. International students are always reaching out. Right now, we have a big Canadian contingent. Canadians are seeing that…these guys can succeed as a student athlete. Very much like what Ben Ogden did at U.V.M. Ten years ago, it wasn’t that way.”

Schwartz isn’t afraid of mixing in international students. “I see it as a positive thing. Bringing different experiences…they love the team atmosphere, because overseas it’s a little bit more individualized. They love being able to study and compete. At the same time, I don’t want to become an international team.”

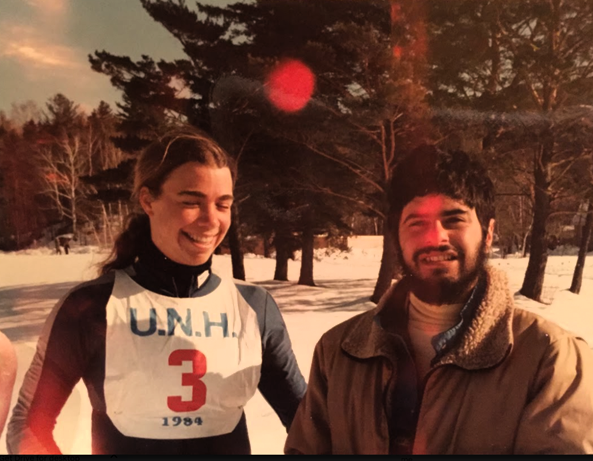

There are a few moments over the last 42 years in particular that stand out to Schwartz. “I do have a few that really make me proud,” he remembered. “One is the first time the team won, Mike Hussey was my first all American, winning that first Carnival (a North Eastern term for tournament or meet) as a young coach of 23 meant something to me. Another moment was Anya Bean, (daughter of his teammate, Howie Bean). Her mom had passed away, and there was a lot of pressure on her, earning all American meant a lot to her and Howie. I’ll remember the look on Howie’s face after she finished her race.”

Schwartz’s message to coaches beginning their careers is simple. “The big one is communication is going to lead you to success, but don’t forget communication is also listening, it’s not talking.” Another thing he’d like to see more of is communication between coaches, and maybe going back in time a little for that. “In the 80s and 90s coaches got together a lot and interacted. Nowadays, we’re all in our wax trailers. I do miss meeting and creating those friendships with other coaches. We can go a whole weekend and not really see each other. As a young coach I learned so much just by observing and listening and talking (to older coaches), Terry Aldrich at Middlebury, John Morton at Dartmouth, Bud Fisher at Williams, Bob Axtell at St. Lawrence. You can gain so much by watching and listening.

The ski world would do well to heed Schwartz’s advice: a little conversation, a little listening, and some camaraderie can go a long way.

Schwartz didn’t have time to ski much while coaching and is looking forward to having the opportunity now in retirement. “I’m looking forward to being able to enjoy the sport that got me into coaching. That first year I’m going to stay local and go for a ski.”

Schwartz summed up his 42 years of coaching this way. “I feel honored to have been able to work at the University of New Hampshire and to work with the athletes that I did. I think their interactions with me made it feel like, while it’s a job, it’s not a job. I’m thanking them now for being able to coach them.” Quite a summation, and quite a legacy for a man who, early on, grasped the importance of team, and the importance of being happy doing what you do . . . for 42 memorable years.