February is here, and Nordic skiers in the Upper Midwest are at a teetering point. Many of us are remaining cautiously optimistic that all we need is “one good snow” to salvage our ski season. The Canadian Birkie, American Vasa, Finlandia, and Vasaloppet USA have already cancelled their races. Many skiers are starting to wonder how races like the Birkie will look this year. What a stark contrast from last year’s record setting snowfall throughout much of the Upper Midwest and this year’s record set in Alaska! The records we’ve set this year are not ones Nordic skiers are excited about. Globally, 2023 was the warmest year in recorded history and we’re enduring extreme conditions locally. December saw lots of rain instead of snow in central Minnesota with high temperatures breaking 50° F. High school Nordic races were canceled every week throughout Minnesota as students roller skied and ran to maintain fitness. In January, the Seeley Hills Classic had to be moved to the Birkie trailhead to use manufactured snow under reduced distance. The Loppet Foundation was unable to generate enough man-made snow to sell ski passes and was forced to make an urgent call for donations. The “First Chance Race” at Mora, MN turned into 10 laps on a 1km loop as warm temperatures limited the Vasaloppet USA’s snow making capability.

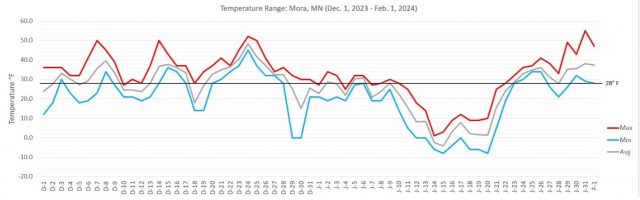

Climate change is wreaking havoc on the ski season. By mid-January, social media discussions about the 2024 Birkie started to ask whether or not it might be wise to have a virtual option, as we did in 2021. As crazy as that may sound, the virtual Nordic ski race is a growing fixture of our sport. While many venues such as the Vasaloppet USA Nordic Center, Theodore Wirth Park, and the American Birkebeiner Ski Foundation (ABSF) have worked as hard as possible to make snow for their major races, climate change data illustrate how this is becoming a greater challenge. For example, at least 14 days in December had low temperatures that were too warm for making snow in Mora, MN (assuming ~28° F is required) and the few cold snaps that did come were followed by days with highs that hit 50° F. Mid-January saw consistently cold temperatures that allowed snow making to proceed for multiple days on end, but a record setting warm spell at the end of the month cancelled out much of those efforts (Figure 1). The Vasaloppet USA Nordic Center in Mora, MN is not the only place in the Upper Midwest struggling with how to maintain our Nordic ski traditions in the face of climate change.

Even after the recent record setting 2022-2023 winter of central Minnesota, virtual ski racing and events are now fixtures on the Nordic landscape. For example, the Lander Nordic Ski Association in Wyoming offers a 9-week Nordic Virtual Challenge for the current winter. USA Nordic has been offering Virtual Nationals since 2018 for U14 and younger athletes. The Noquemanon in Michigan’s UP offered a virtual option for the 2024 race. And Mecca Trails in Mercer, WI offered both in-person and virtual options for their 2023 Winterfest and only a virtual option in 2024 after they had to cancel the in-person event. These examples highlight different kinds of virtual options, ranging from single-day competitions, to multiweek events, to better-than-nothing alternatives when snow doesn’t come. While it may seem like virtual races are a second-best that pale in comparison to in-person races with all the atmosphere and excitement we’ve come to love, they may become a common alternative to race cancellations as we adapt to the effects of climate change.

What do people think?

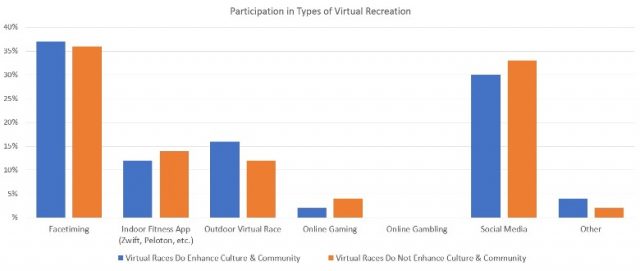

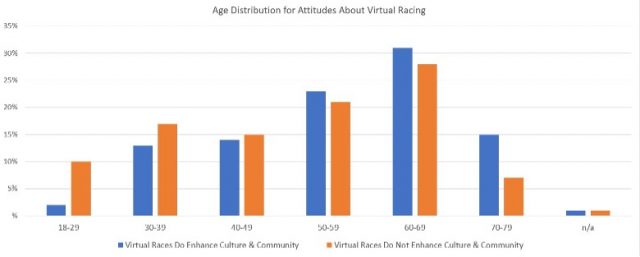

In 2021, we surveyed 1300 cross-country skiers throughout the United States and abroad and shared the results of how skiers defined their culture and community (Article 1 link) and whether or not skiers actually liked virtual racing (Article 2 link). In this article we tackle the question of how virtual racing impacts our shared culture and community in light of climate change. At least 1200 respondents to our survey provided their opinions on whether or not virtual racing enhanced their engagement with cross-country culture and community. Of these respondents, about 40% said it did enhance engagement, about 30% said it did not, and the remainder were unsure. Interestingly, the ways in which skiers participate in other online or virtual activities was almost identical between the groups. They use online virtual platforms to face time with friends and family, post to social media, and do virtual races and maintain fitness on apps like Zwift, Rouvy and Peloton (Figure 2). There is a very strong similarity in how everyone engages with social media and virtual activities; however, there seems to be a real split in what these activities mean to each respondent group. This may be structured by a larger sense of how people view “online communities” or the ability for us to use social media to actively participate in culture. Unexpectedly, the results are counter-intuitive in that more of the oldest generation (70-79) feels that virtual racing enhances culture and community while the youngest generation (18-29) feels the opposite (Figure 3). Who would’ve thunk it?

For the 30% of respondents that do not feel like virtual events enhance engagement with

Nordic skiing culture and community, almost half of them objected to the lack of interpersonal engagement with other racers. These respondents felt that culture and community grow through the authentic shared experience of an in-person race, not from solo workouts (i.e., solo virtual race). These respondents also felt the excitement and atmosphere of racing on the actual course is an important element to building shared culture and community. On the other hand, the 40% who felt virtual options did build culture and community, emphasized that sharing results with others online and in person was meaningful. For these folks, the virtual event is about a lot more than doing a race on a single day. They recognized how engaging in the organization, planning, and volunteering needed to put on events actually grows Nordic ski community. Many of these folks valued the fact that virtual events provide a basic opportunity to engage in ski culture even if removed from the traditional venues. When ski clubs organized virtual events, and friends and family had an opportunity to ski together, many virtual racers felt very engaged in our culture and community. Finally, 7% of the respondents noted all of the positive comments they received from others about their race bibs and signage posted at local venues that hosted virtual events. This increased visibility serves to spread the culture and community of the home organization into far flung communities hosting virtual satellite events.

Skiscape

With each of the major reasons why virtual events don’t enhance community and culture, there is an alternative perspective that sees how they do – with one exception. There was no counter point to the objection that virtual events do not use “the real course” and lack the “atmosphere” of the in-person, live event. People develop communities by engaging in specific outdoor activities with defined rules, norms, and etiquette. When these shared activities occur in the same space, cultural landscapes are constructed. This results when shared meanings are associated with specific physical and natural elements that convert a neutral “space” into a meaningful “place.” For example, 51 weeks out of the year, downtown Hayward, WI or Mora, MN are collections of nice shops, restaurants, and businesses to visit. But, when the Birkebeiner and Vasaloppet races occur, these downtown spaces become cultural landscapes where the cross-country community practices our culture. More than just a downtown celebration, our cultural landscapes are unique because they also include the experience of the race course.

An important element of building community is the camaraderie developed among a group that participates in a physically demanding activity under challenging environmental conditions. Following the event, skiers talk about the race and create stories of what occurred based on their personal lived experience of the same day at the same place. One outcome is that sections of race courses or trails take on names and develop reputations with specific attributes (e.g., Steep Beast, The Wall, Heckler’s Hill, Bowling Alley, Roger’s Ridge). For marathon ski races, the unique landscape and environmental conditions of the day play crucial roles in the physical experience and shared meaning. The fact that the physical activity and shared experience must occur on a substrate of snow that has been specifically groomed, and sometimes produced, for the very purpose of holding the race, results in a special kind of cultural landscape that we have dubbed a “skiscape.” The skiscape is a unique type of cultural landscape that results from the ephemeral combination of natural environment, season of the year, climate and weather patterns, human behavior, and cultural meaning. A fantastic example of capturing a skiscape on video was done by the ABSF for the 2018 American Birkebeiner that can be viewed and experienced virtually online (Figure 4). The unique atmosphere generated at a skiscape cannot be reproduced by a virtual event. When climate change negatively impacts a skiscape, members of the associated community will need to adapt. One way that we have adapted is through virtual races.

On-Ramps and Impacts

In 2021, many race organizations offered virtual racing alternatives for their major events in response to the social distancing requirements of the pandemic. The winter of 2023-2024 is the first time we are faced with using virtual racing as a direct response to climate change. When dealing with a major health crisis, many in the cross-country ski community embraced virtual options as a way to participate and stay connected to our sport. Facing the current climate crisis, will we make a similar choice?

Based on data provided by the ABSF for the pandemic-stricken 2021 race season, 50% of the skiers racing the Birkie, Korte, and Prince Haakon chose to do a virtual option. This was clearly affected by the pandemic restrictions. What is really important to consider, and may be applicable to a non-pandemic year, is that 7% (490) of the total number of racers for all three ABSF events (7,097 total registrants) used the virtual option as an ‘on-ramp’ to try a new race. Of the 2,419 total virtual Birkie skiers, 9% (214) were first-timers; 20% (189) of the virtual Kortelopet skiers were first-timers; and, 87 (57%) of the 152 virtual skiers of the Prince Haakon were first-timers. A random sample of first-time Birkie skiers who chose the virtual option indicates about 35% used the opportunity to increase their distance from doing the 29 km Korte in 2020 to the longer Birkie in 2021. The remainder of virtual first-time Birkie skiers had not completed an ABSF race in 2020. This is significant because it illustrates how virtual events can increase participation of new skiers to the sport and provide an opportunity for current skiers to try longer distances.

Now we are in 2024 and facing a rapidly changing climate. Ski race organizers are grappling with environmental responsibility at multiple scales. The International Ski and Snowboard Federation (FIS), that governs professional World Tour cross-country ski racing, signed the Sports for Climate Action Framework to generate broader climate awareness and global action through winter sports with a plan to achieve net-zero emissions by 2040 (International Ski and Snowboard Federation 2021). The nonprofit U.S. organization Protect Our Winters (POW) motivates snow sport enthusiasts to lobby state and federal governments to enact climate- positive legislation. POW recognizes that meaningful cultural change within the U.S. is required to make the long-term structural changes necessary to limit global warming (Protect Our Winters 2022). And this is a concern in the Upper Midwest as well. After securing corporate sponsorship from Enbridge Energy that operates oil and gas pipelines from Canada to the U.S., the ABSF abruptly ended the partnership due to environmental objections by its members and the larger cross-country ski community (Star Tribune 2021).

Greenland Moment?

Snow-making has been pushed to its limit in the Upper Midwest. After two weeks of warm temperatures that prevented artificial snow making and no natural precipitation, the Vasaloppet USA was forced to cancel its hallmark race. The Loppet Foundation is working tirelessly to make and preserve enough snow at Theodore Wirth Park to host an FIS World Cup race in downtown Minneapolis. The ABSF is producing as much snow as they possibly can while rapidly approaching the deadline for making a final decision on their race formats. All of this effort costs money, consumes water, and has an environmental impact. Meanwhile, discussions on social media have begun to debate the pros and cons of using virtual options as an adaptive strategy to warm winters. Those in favor of using a virtual option for races during the current low/no snow winter question the expense and logic of leaving regions with lots of snow to travel long distances only to ski in poor conditions. The carbon footprint of this kind of travel also comes into question. Those opposing virtual options point out the huge economic impact that could be suffered by local host communities if the racers stayed home. The shared community, camaraderie and festival that occurs around the in-person race is also absent with a virtual format. Many skiers also feel that it’s important to show up and support the organization that is hosting the event because of all the hard work and planning it requires.

In our first article, we discussed the image of Vikings in our modern-day conception of cross- country ski culture. The reason why Viking settlements in Greenland disappeared during the Medieval period is relevant to how we think about adapting and preserving our Nordic ski culture today. While the phenomenon was complex, two key factors were climate change and cultural traditions. In short, the warmer period that allowed the Vikings to settle Greenland turned cold as the Earth entered the Little Ice Age. This significantly impacted their ability to maintain farms modeled on a European tradition. At the same time, Viking settlers maintained long standing cultural traditions that followed economic trends established in Iceland and greater Scandinavia. While native Thule and Inuit peoples adapted to the colder climate and thrived in Greenland, the Viking descendants were locked into a way of life that eventually forced them to leave or die. Are cross-country skiers experiencing a “Greenland moment”? In the fourth and final article in this series, we will address what race organizers can do to grow culture and community in the midst of increasingly unpredictable winter ski seasons. We will look at how far people are willing to go for a race, alternative models for hallmark races, and whether we can maintain our friluftsliv lifestyle.